Exploding Stars: The Spectacular Death of Giants

- Elle

- 1 day ago

- 9 min read

Somewhere in the universe right now, a star is exploding. Not just burning. Not just flickering. Exploding with the force of 100 trillion trillion trillion megatons of TNT, releasing more energy in a few seconds than our Sun will produce over its entire 10 billion year lifetime, blasting its guts across space at speeds of 50 million miles per hour, and briefly outshining an entire galaxy of 100 billion stars.

We call these explosions supernovae (singular: supernova), and they happen about once every 10 seconds somewhere in the observable universe. They're the most violent deaths stars can experience. And weirdly, they're also the reason you exist.

Every atom in your body heavier than hydrogen (which is basically all of them) was forged inside a star and scattered across space by a supernova explosion. The iron in your blood, the calcium in your bones, the oxygen you breathe, all of it came from dying stars that exploded billions of years ago.

But why do stars explode in the first place? The answer depends on what kind of star we're talking about and how it lived its life. Let's dive into the spectacular science of stellar death.

What Makes a Star Stable (Until It Isn't)

Before we can understand why stars explode, we need to understand why they don't explode all the time.

Stars spend most of their lives in a delicate balance between two opposing forces:

Gravity (pushing inward): The star's massive weight trying to crush it into a point. Every bit of matter in the star is pulling on every other bit, trying to make the star collapse.

Pressure (pushing outward): Heat and radiation from nuclear fusion in the star's core pushing outward, trying to make the star expand.

As long as these forces balance, the star is stable. It's in what scientists call "hydrostatic equilibrium." Think of it like a tug-of-war where both teams are equally strong, so the rope doesn't move. The fusion happening in the star's core provides the outward pressure. In the core of a typical star like our Sun, hydrogen atoms are being fused together to make helium, releasing enormous amounts of energy. This energy heats the star and creates the pressure that prevents gravitational collapse.

But here's the catch: fusion can't last forever. Eventually, you run out of fuel. And when you run out of fuel, the outward pressure drops. Gravity wins. The star collapses.

What happens next depends entirely on how massive the star is.

The Two Ways Stars Explode

There are two fundamentally different ways stars can explode, and they produce very different types of supernovae.

Type 1: Core Collapse (Type II, Ib, and Ic Supernovae)

This is the explosion of a massive star that has run out of nuclear fuel. To go out this way, a star needs to be at least 8 times more massive than our Sun (but no more than about 40-50 times the Sun's mass, beyond which things get even weirder).

Here's how it works:

Step 1: The Onion Star

Massive stars don't just fuse hydrogen into helium and call it a day. They have enough mass and temperature to keep fusion going with heavier and heavier elements.

First, hydrogen fuses into helium in the core. Then, when the hydrogen runs out, the core contracts and heats up until it's hot enough to fuse helium into carbon. Then carbon into neon. Then neon into oxygen. Then oxygen into silicon. Finally, silicon into iron.

Each stage happens faster than the last. A massive star might spend millions of years fusing hydrogen, but only a few hundred years fusing helium, and just days fusing silicon into iron. By the time a massive star is about to die, its interior looks like an onion with layers of different elements burning around an iron core.

Step 2: Iron, the Dealbreaker

Iron is where the process stops cold. Here's why: every fusion reaction up to iron releases energy. That's what powers the star. But fusing iron into heavier elements requires energy instead of releasing it.

This is a huge problem. As soon as the core becomes iron, fusion can't provide any outward pressure. The energy supply is gone. Gravity has won.

Step 3: The Collapse

Without the support of fusion energy, the iron core collapses catastrophically. And when I say catastrophically, I mean in less than one second, a core the size of Earth (but with a mass like our Sun) collapses into a ball of neutrons just 12 miles across.

The core collapses so fast that the outer parts are moving at up to 23% the speed of light. The temperature skyrockets to 100 billion degrees Fahrenheit. That's hotter than you can really comprehend.

At these extreme conditions, several bizarre things happen:

Photodisintegration: The super-high-energy gamma rays produced in the collapse are so powerful they literally tear apart iron nuclei, undoing hundreds of thousands of years of fusion in seconds.

Electron capture: Protons and electrons are forced together to form neutrons, releasing floods of ghostly particles called neutrinos.

Neutrino production: The newly forming neutron star is so hot (100 billion degrees) that it radiates enormous numbers of neutrinos to cool down.

Step 4: The Bounce

The collapse finally halts when the core becomes so dense that neutrons themselves resist being compressed further. It's called neutron degeneracy pressure, and it's the only thing in nature that can stop a gravitational collapse this extreme (at least for cores up to about 5 times the Sun's mass).

When the collapse stops, it doesn't stop gently. The core rebounds like a super-ball hitting concrete, creating a massive shockwave that races outward through the star.

Step 5: The Explosion

This shockwave, powered by neutrinos and the rebound, blasts through the star's outer layers at incredible speeds (over 50 million miles per hour). The energy is so extreme that it triggers a whole new wave of fusion in the star's outer shells, creating elements heavier than iron (like gold, platinum, and uranium) that couldn't be made during the star's normal lifetime.

When the shockwave hits the star's surface, the star explodes as a supernova, blasting its guts across space. The explosion can be as bright as several billion Suns combined and can be seen from billions of light-years away.

Step 6: The Remnant

What's left behind depends on the mass of the core:

If the core is less than about 5 solar masses, you get a neutron star, an object so dense that a teaspoon of its material would weigh about a billion tons on Earth. Neutron stars sometimes show up as pulsars, rapidly spinning lighthouses of radiation.

If the core is more massive than about 5 solar masses, not even neutron degeneracy can stop the collapse. The core keeps collapsing into a black hole, an object so dense that not even light can escape its gravity.

Type 2: Thermonuclear Runaway (Type Ia Supernovae)

The other way stars explode is completely different. This happens when a white dwarf star goes nuclear.

What's a white dwarf?

When a star like our Sun runs out of hydrogen and helium to fuse, it doesn't have enough mass to continue fusion with heavier elements. Instead, it gently sheds its outer layers (creating a planetary nebula) and leaves behind a hot, dense core about the size of Earth but with about half the Sun's mass. This is a white dwarf.

White dwarfs are made mostly of carbon and oxygen. They're incredibly dense (a sugar-cube-sized chunk would weigh about as much as a car) and they're supported against collapse by electron degeneracy pressure, not by fusion. They're basically the burnt-out embers of dead stars, slowly cooling over billions of years.

Most white dwarfs just sit there cooling forever. But some get a second chance at glory.

The Binary System Setup

If a white dwarf has a companion star orbiting nearby, it can steal material from that companion. The white dwarf's gravity pulls gas (mostly hydrogen and helium) from the other star onto itself in a process called accretion.

Slowly, over thousands or millions of years, the white dwarf gains mass. And there's a magic number in physics called the Chandrasekhar limit: about 1.4 times the mass of the Sun. If a white dwarf accumulates enough mass to exceed this limit, something dramatic happens.

The Runaway Fusion

As the white dwarf approaches the Chandrasekhar limit, the pressure and temperature in its core rise. Eventually, they rise enough to ignite carbon fusion.

But here's the problem: the white dwarf is supported by electron degeneracy, not gas pressure. This means when fusion starts, it doesn't make the star expand and cool (like it would in a normal star). Instead, the carbon starts fusing into heavier elements (neon, magnesium, silicon, and ultimately iron-group elements like nickel), but the pressure keeps building without the star expanding.

This creates a runaway fusion reaction. The fusion produces heat, which accelerates more fusion, which produces more heat, in a feedback loop that happens incredibly fast. Within seconds, the entire white dwarf is engulfed in nuclear fusion. The energy released is so enormous that it completely disintegrates the star. There's no neutron star left behind. No black hole. The entire star is blown apart.

The Brightness

Type Ia supernovae are remarkably consistent in brightness because they all happen at about the same mass (the Chandrasekhar limit). This makes them useful as "standard candles" for measuring cosmic distances. In fact, observations of Type Ia supernovae led to the discovery of dark energy and won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2011.

How to Tell Them Apart

Astronomers classify supernovae based on their spectra (the specific wavelengths of light they emit):

Type II supernovae show hydrogen in their spectra. These are core collapse supernovae from massive stars that still had their hydrogen envelopes when they exploded. They happen in regions with lots of young, massive stars like spiral galaxy arms.

Type Ib and Ic supernovae are also core collapse explosions, but from massive stars that had already lost their outer hydrogen layers (Type Ib still has helium, Type Ic has lost even that). These stars were so massive and hot that stellar winds blew away their outer layers before they exploded.

Type Ia supernovae show no hydrogen and have strong silicon absorption lines. These are the thermonuclear explosions of white dwarfs. They can happen anywhere, even in elliptical galaxies full of old stars, because white dwarfs can take billions of years to accumulate enough mass to explode.

What Supernovae Create

Supernovae aren't just destroyers. They're also creators. In fact, they're essential to life.

Heavy Elements: All the elements heavier than iron in the universe (gold, silver, platinum, uranium, etc.) were created in supernova explosions. The extreme conditions during the explosion are the only places with enough energy to make these elements.

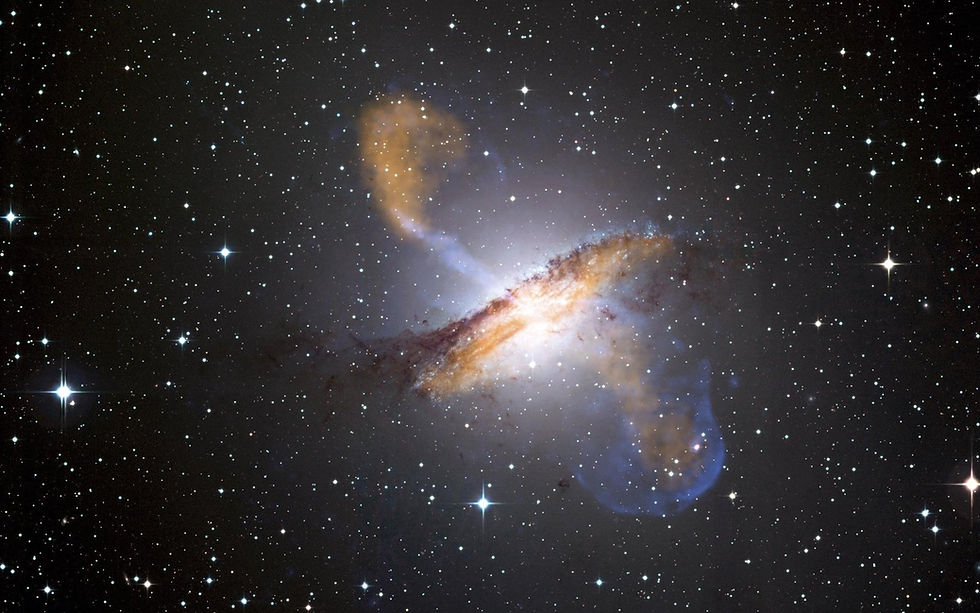

Nebulae: The expanding debris from a supernova creates beautiful structures called supernova remnants. The Crab Nebula, for instance, is the remnant of a supernova that exploded in 1054 CE and was visible from Earth in broad daylight.

Star Formation: The shockwaves from supernovae can compress nearby gas clouds, triggering the formation of new stars. Our own solar system might have formed from a cloud that was compressed by a nearby supernova.

Neutron Stars and Black Holes: These extreme objects teach us about physics in conditions we can never replicate on Earth.

The Elements of Life: Carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, iron, calcium, everything that makes up your body except hydrogen was created in stars and scattered by supernovae. You are literally made of star stuff.

Can We See Supernovae?

Supernovae in our own Milky Way galaxy are rare, happening only about once per century on average. The last one visible to the naked eye was in 1604 (Kepler's Supernova). But astronomers discover about 2,000 supernovae every year in other galaxies by monitoring millions of galaxies and looking for new bright spots that appear suddenly.

In 1987, a supernova (SN 1987A) exploded in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a nearby dwarf galaxy. It was visible from Earth without a telescope and gave scientists an unprecedented opportunity to study a supernova up close. Neutrinos from the explosion were detected on Earth, confirming theories about core collapse.

Famous Future Supernovae

Some stars we can see in the night sky are destined to explode as supernovae. The most famous is Betelgeuse, the red supergiant star that marks Orion's shoulder. It's a massive star (about 20 times the Sun's mass) that has already fused its hydrogen and helium and is nearing the end of its life.

When Betelgeuse explodes, it will be spectacular. It's only 640 light-years away (very close in cosmic terms), so when it goes supernova, it will be brighter than the full moon in our sky and visible during the daytime.

The catch? It might have already exploded. Light takes 640 years to reach us from Betelgeuse, so if it exploded 400 years ago, we wouldn't know for another 240 years. Or it might not explode for another 100,000 years. Stars are unpredictable near the end.

The Bottom Line

Stars explode for two main reasons:

Massive stars (at least 8 solar masses) run out of fuel, their iron cores collapse in less than a second, and the rebound creates a shockwave that blasts the star apart. These core collapse supernovae leave behind neutron stars or black holes and scatter heavy elements across space.

White dwarfs in binary systems accumulate mass until they reach a critical limit, triggering runaway fusion that completely disintegrates the star in a thermonuclear explosion. These Type Ia supernovae leave nothing behind but expanding gas.

Both types release staggering amounts of energy, create heavy elements, trigger new star formation, and enrich the universe with the building blocks of planets and life.

The iron in your blood came from a supernova. The calcium in your bones came from a supernova. The oxygen you're breathing right now came from a supernova. You are the universe's way of knowing itself, made from the ashes of dead stars that exploded billions of years before you were born.

And somewhere out there, right now, another star is exploding, scattering the materials that will someday make new solar systems, new planets, and maybe new life. Stars die so that we can live. And that's pretty extraordinary.

Sources

Chandra X-ray Observatory. Supernovas & Supernova Remnants. Retrieved from https://chandra.harvard.edu/xray_sources/supernovas.html

COSMOS - Swinburne University. Core-collapse. Retrieved from https://astronomy.swin.edu.au/cosmos/C/core-collapse

Las Cumbres Observatory. Supernova explosions. Retrieved from https://lco.global/spacebook/stars/supernova/

Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics. Core-collapse supernovae. Retrieved from https://www.mpa-garching.mpg.de/84411/Core-collapse-supernovae

NASA Imagine the Universe. Supernovae. Retrieved from https://imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/science/objects/supernovae2.html

The Schools' Observatory. Types of Supernovae. Retrieved from https://www.schoolsobservatory.org/discover/projects/supernovae/typeI

U.S. Department of Energy. DOE Explains...Supernovae. Retrieved from https://www.energy.gov/science/doe-explainssupernovae

Wikipedia. (2025). Supernova. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Supernova

Wikipedia. (2025). Type II supernova. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Type_II_supernova

Comments